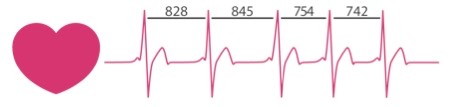

A normal healthy heart does not tick evenly like a metronome.

We know that the normal resting rhythm of the heart is highly variable rather than monotonously regular.

Even if your heart rate is for example 60 beats per minute, that doesn’t mean that your heart beats once every second. The time interval between consecutive heartbeats is constantly changing. This naturally occurring variation is called heart rate variability (HRV).

The intervals between your heartbeats is measured in milliseconds and you can actually feel the difference between the intervals.

Place a finger gently on your neck and find your pulse. You should feel that the longest intervals take place when you exhale, and the shortest intervals when you inhale.

HRV is regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and its sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. The sympathetic branch, the stress or fight system, activates stress hormone production and increases the heart’s contraction rate and force and decreases HRV, which is needed during exercise and mentally or physically stressful situations.

The parasympathetic side is characterized as the rest and digest system that allows the body to power down and recover “once the fight is over”. The parasympathetic branch slows the heart rate and increases HRV to restore homeostasis after the stress passes.

This natural interplay between the two systems allows the heart to quickly respond to different situations and needs.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the ANS are continually interacting to maintain cardiovascular activity in its optimal range and to permit appropriate reactions to changing external and internal conditions.

The analysis of HRV serves as a dynamic window into the function and balance of the ANS. HRV can be considered as an important indicator of health and fitness. It reflects our ability to adapt effectively to stress and environmental demands.

HRV is an interesting and non-invasive way to identify imbalances in the ANS. If a person’s system is in more of a fight-or-flight mode, the variation between subsequent heartbeats is low. If one is in a more relaxed state, the variation between beats is high. In other words, the healthier the ANS the faster you are able to switch gears, showing more resilience and flexibility.

People with higher HRV are in better general physical health because the vagus nerve, the main branch of the parasympathetic nervous system, reduces inflammation, which is the key to many chronic diseases. Activity of the vagus nerve can be measured and indexed by HRV.

Having high HRV is associated with higher emotional well-being, including being correlated with lower levels of worry and rumination, lower anxiety, and generally more regulated emotional responding.

Individuals with higher HRV appear to be better at regulating their emotions. High rates of HRV are also associated with better decision-making. HRV is positively correlated with brain activity in regions crucial for decision-making such as the prefrontal cortex.

Over the past few decades, research has shown a relationship between low HRV and worsening depression or anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, and cancer.

A study of De Couck et al. showed preliminary results demonstrating that two forms of slow-paced breathing can increase vagal nerve activity and consequently HRV. The most scientifically supported mechanism to explain the effects of deep breathing on vagal activity is the strengthening of homeostasis in the baroreceptors.

In another study, De Couck and colleagues hypothesized a possible bi-directional relation between cancer and vagal nerve activity after discovering lower HRV in cancer patients compared to those in healthy persons. So, HRV can be seen as a significant prognostic factor in cancer.

Chronic pain patients also exhibit low HRV ratings, having lower vagal activity compared to healthy persons. The vagus nerve plays an important role in pain modulation by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress, and sympathetic activity. Vagal nerve activity also activates brain regions that can oppose the brain “pain matrix”. And finally, vagal activation influences positively the analgesic effects of opioids.

HRV is a marker of biological aging. HRV decreases with aging. Gender also influences HRV. The differences between sexes are most pronounced in subjects <30 years of age with HRV of young male subjects being significantly greater than that of age-matched female subjects. These differences disappear by the age of 50.

Genetic factors explain about 30% of the overall HRV level. However, people can improve their individual HRV by improving their health, fitness, stress management, and recovery skills.

So, tracking your HRV, may be a great tool to motivate behavioral change. HRV measurements can help create more awareness of how you live and think, and how your behavior affects your nervous system and bodily functions. While it obviously can’t help you avoid stress, it could help you understand how to respond to stress in a healthier way.

Luc Vanderweeen

Master of Science in Spinal Manual Therapy and

Physiotherapy

Rug-Schouder-Nekcentrum, Schepdaal, Belgium

Pain in Motion Research Group

2019 Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

De Couck, M., Caers, R., Musch, L., Giangreco, A., Gidron, Y. (2019). How breathing can help you make better decisions: Two studies on the effects of breathing patterns on heart rate variability and decision-making in business cases. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY, (139), 1-9.

De Couck, M., Caers, R., Spiegel, D., Gidron, Y. (2018). The Role of the Vagus Nerve in Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic and a Comprehensive Review. Journal of Oncology

De Couck, M., Nijs, J., Gidron, Y. (2014). You May Need a Nerve to Treat Pain The Neurobiological Rationale for Vagal Nerve Activation in Pain Management. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 30 (12), Art.No. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000071, 1099-1105.

Umetani K1, Singer DH, McCraty R, Atkinson M.(1998) Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: relations to age and gender over nine decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Mar 1;31(3):593-601.

Campos , M (2017) Heart rate variability: A new way to track well-being. Harvard Health Blog.