Successfully alleviating pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) or in patients with persisting pain after a total knee replacement (TKR) remains a huge challenge. This phenomenon might be attributed to the heterogeneity of the disease.

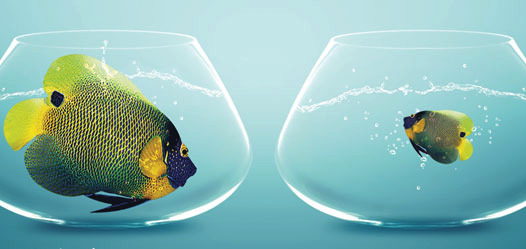

It has been proposed that OA is a syndrome comprised of multiple distinct phenotypes rather than a single disease (Karsdal et al. 2016). A phenotype in knee OA can be defined as a collection of observable traits (i.e. aetiologic factors, risk factors) that can identify and characterize a subgroup in a defined population.Deveza and colleagues (2017)stated that identifying OA phenotypes would allow targeted treatment for specific subgroups and ultimately the identification of more efficacious treatments.

Dell’Issola and colleagues (2016)reviewed the identification of clinical phenotypes in knee OA. In total, they described the existence of six phenotypes:

As mentioned above, this heterogeneous patient population requires individualized treatment instead of a one-size-fits-all treatment approach:

The aforementioned phenotypes and their specific treatment approaches are mainly useful in the conservative management of knee OA. But what if conservative treatment fails?

TKR surgery is the most common surgical treatment for knee OA. Even though it is an effective surgical treatment for end-stage knee OA and the majority of patients with knee OA report significant pain relief and functional improvement, up to 30% of patients undergoing a TKR are dissatisfied with the postsurgical outcome (Williams et al. 2013). Better insight into factors that can predict poor outcome after surgery may be helpful in screening whether preceding/additional therapeutic modalities are required in order to increase success after surgery.

It seems that we are on the right track with identifying knee OA phenotypes in order to individualize our conservative treatment approach. Let us now go further and examine the predictive value of these phenotypes for TKR outcome, to prevent chronic postsurgical pain from occurring!

What is your opinion about this topic? Please let me know by filling out this poll: https://linkto.run/p/QV7YMYU0

Lotte Meert

PhD researcher at Antwerp University, Antwerp, Belgium

2018 Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

1. Karsdal MA, Michaelis M, Ladel C, et al. Disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis (DMOADs) of the knee and hip: lessons learned from failures and opportunities for the future. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 24(12): 2013-21.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27492463

2. Deveza LA, Melo L, Yamato TP, Mills K, Ravi V, Hunter DJ. Knee osteoarthritis phenotypes and their relevance for outcomes: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017; 25(12): 1926-41.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28847624

3. Dell'Isola A, Allan R, Smith SL, Marreiros SS, Steultjens M. Identification of clinical phenotypes in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17(1): 425.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27733199

4. Nijs J, Goubert D, Ickmans K. Recognition and Treatment of Central Sensitization in Chronic Pain Patients: Not Limited to Specialized Care. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2016; 46(12): 1024-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23777807

5.Xu S, Chen JY, Lo NN, et al. The influence of obesity on functional outcome and quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J2018; 100-B(5): 579-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29701098

6. Eitner A, Pester J, Vogel F, et al. Pain sensation in human osteoarthritic knee joints is strongly enhanced by diabetes mellitus. Pain 2017; 158(9): 1743-53.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621703

7. Williams DP, O'Brien S, Doran E, et al. Early postoperative predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2013; 20(6): 442-6.